Offleash Podcast: Indigenous reporting

Best Journalism on...

Paper Trolls

Hate mail is an unwritten tradition in journalism, especially for writers covering diverse issues

A white envelope with the words “Clean up Canada! No more Immigration!” appeared in Ashante Infantry’s mail slot. What should have been a dot in the second exclamation point was a swastika. The Toronto Star reporter opened it to find some of her clippings taped together. An arrow connected an image of a Black man to a handwritten message scrawled on a white piece of paper, part of which read, “I say send the lazy bastard back on the first banana boat out!”

As a reporter who has covered immigration and race issues, Infantry used to receive these letters for years. She used to throw them away. Then she decided to hang onto some of them, to use as teaching aids. Or if, “in the future, I would need to remind myself about these kind of things happening.”

She’s not alone. Receiving hate mail is an unwritten tradition in journalism, especially for writers who often cover sensitive issues like race, immigration, gender and religion, to name a few. Jim Rankin, a Star reporter-photographer who has written extensively on race issues, calls those who send such hateful comments—online or via snail mail—“angry pyjama people,” because he pictures them writing in their basement in their PJs.

This problem is by no means particular to the Star. Trolling is, unfortunately, an industry-wide experience that spans both decades and media. When post was the main form of communication, people took the time to clip articles, photocopy them, tape them together and attach their own comments to the collage before fitting it neatly into a small envelope. Today, with tweets, comment sections and emails, less time is needed online.

Such messages may not be directly threatening, but they are unquestionably disturbing and, for many, insulting.

Listen to Ashante Infantry on being accustomed to hate mail

Nicholas Keung, the Star’s immigration reporter, doesn’t look at that type of mail anymore, though he receives it on a regular basis. Straight to the trash is his approach. “There’s a range of these negative comments that are just outright racist,” he says. He gets emails and phone calls about how horrible his stories are and how their subjects do not warrant sympathy or empathy.

A regular correspondent sends him a package of story clippings where ethnic labels are underlined in red marker: Somali. Black. Occasionally, they’re labelled terrorists. “I think people today have difficulty accepting that Canada is no longer monocultural,” says Keung.

Infantry chooses not to be on social media, partly because she believes that journalists will be attacked just because a small group of people feel the need to hate. “As a Black woman, I get enough of that in subtle and overt ways,” says Infantry. “If I can avoid it professionally, I prefer to do that.”

Listen to Ashante Infantry’s most memorable hate mail experience

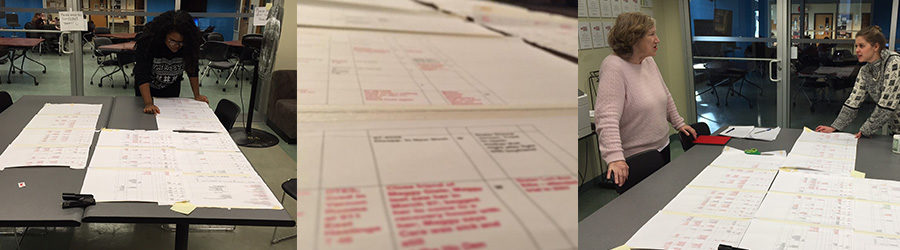

Much of the material in the photo gallery below is from the 1990s and the early 2000s, when journalists regularly received snail mail. After being inundated with it for years, many journalists have become accustomed to it. The few letters that still make it to their desks are thrown away. Journalists try to ignore most online hate, even as social media amplifies the trolls’ voices. Yet, while the medium has changed, the challenge is the same. And it’s hard to deny the power words can have after looking through these letters.

A student at the Ryerson School of Journalism, which I chair, asked me recently whether I think the school is doing enough to help young journalists understand diverse communities and how to cover them.

My answer: we’re working on it.

It’s important that we do. Journalists exist to explain the world to the world—a world of almost infinite variety. If journalists approach their task with an expectation that people are or should be alike, there’s no chance of the job being done well.

This makes understanding and covering diversity a core skill for journalists, at least in countries like Canada. Figuring out how to teach this and other core journalistic skills, however, is complicated.

Until fairly recently, Ryerson’s undergraduate journalism program was heavily “streamed,” and students’ paths consisted mostly of required courses. We were proud to announce in 1997 that all students would take a course in covering diversity. Ironically, by the time that course won a Canada Race Relations Foundation award in 2003, our ideas about teaching had changed. This and several other course requirements were eliminated over the following years, amid some controversy.

Until fairly recently, Ryerson’s undergraduate journalism program was heavily “streamed,” and students’ paths consisted mostly of required courses. We were proud to announce in 1997 that all students would take a course in covering diversity. Ironically, by the time that course won a Canada Race Relations Foundation award in 2003, our ideas about teaching had changed. This and several other course requirements were eliminated over the following years, amid some controversy.

We now think that instead of putting a vital area of training into a single-course silo, it should be woven through the curriculum, introduced in the first weeks of study and reinforced until graduation. Even Ryerson’s required ethics and law course will soon disappear: rather than siphoning free expression, human rights and libel into 12 classes in a single semester, we want these topics to take their rightful place alongside vital practical skills such as interviewing, writing, multimedia production and, yes, covering diversity.

Understood this way, Ryerson students should learn to cover diversity by, well, covering diversity—by reporting stories on the streets of one of the world’s most diverse cities. By getting feedback and evaluation on the quality of their work, and by participating in candid discussions about the issues encountered, they learn to be better observers, interpreters and citizens.

In recent months, upper-level undergraduates have written or produced stories on how micro-aggressions hurt, on the dearth of women cartoonists, on personal support workers’ interactions with people with disabilities, on an Indigenous student’s anxiety over her lighter skin tone, on sex-worker peer groups and Queer axe-throwers and Arabic calligraphers in Canada. A course on international journalism has discussed reporting across cultures and economic marginalization. Students in Reporting Religion have examined Tibetans protesting against the Dalai Lama and the experience of Mormon elders on mission in Toronto. An editing class discussed sexist and racist language, and a health and science reporting course looked at homophobia. Meanwhile, school-wide events last semester explored the online and other harassment of women, the status of women in newsrooms, and coverage of Indigenous issues.

Does all this mean that, from a curricular point of view, we have “got diversity covered?”

I wish.

Some teachers and students are, of course, more ready and willing than others to address sensitive issues, and the manner of this engagement varies from helpfully diverse to, sadly, the reverse. Sometimes issues of diversity are swept aside or handled with a dismissive reference to “political correctness,” a term that lost useful meaning before most of our students were born. Occasionally, judgment calls and remarks made in meetings and classes still leave us wondering just where people have been living for the past couple decades or so. Actions and comments that hurt others or reveal insensitivity to difference usually lead to difficult discussions, whether in private or in larger groups—as they should.

So, we’re still learning.

Last year, for example, we asked representatives of the university’s Office of Equity, Inclusion and Diversity to speak with our faculty about how to establish a culture of respect in the classroom—an atmosphere where everyone gets a fair say and no one’s an outsider. It was an awkward discussion, but it helped us understand more clearly how seemingly minor incidents can leave people feeling smaller, and how offhand or humorously intended remarks have the effect of enforcing the majority’s cultural reference points.

This year, spurred by a call to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the journalism school is building a plan to raise students’ awareness of Indigenous issues through targeted assignments, new course content and a day-long workshop for journalism faculty members about Aboriginal culture, history and representation.

We also need to get closer to a position where all students, regardless of identity, see themselves mirrored in a teacher’s culture and heritage at some point in the program. Given the number of cultures and electives in our department, we’re unlikely to make it all the way there, but, in our hiring efforts and selection of guest speakers, we can and will try harder.

And in doing so, we’ll keep learning.

Join the conversation on Twitter using #whydiversity.

Fixing a Broken Mirror

Tired of the warped reflection presented by mainstream news, Maureen Googoo took Indigenous reporting into her own hands

When colleagues talk to Googoo about diversity in journalism, she tells them the same story each time. In j-school at Ryerson University in 1992, a professor said her pitches weren’t relevant. Articles about Aboriginal communities don’t resonate with mainstream readers, the teacher told her—“advice” she would later hear from many colleagues. “But I don’t want to tell stories to another audience,” Googoo says. Today, she writes for, and about, Aboriginal Peoples.

After graduating, Googoo worked as a reporter for CBC, Halifax’s The Chronicle Herald and Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) before completing a graduate degree in journalism at Columbia University. That’s where she found the inspiration to leave established newspapers and TV stations and start her own initiative.

Since launching Kukukwes.com in August, Googoo has become a prominent Indigenous voice in Atlantic Canada. She has been travelling across the region, covering stories such as the election of chiefs in various First Nations bands and the Sipekne’katik’s opposition to a gas storage project in Nova Scotia. “I have a very specific interest,” she says, “and a very niche audience that is interested.”

Meaningful diversity requires letting a whole community see itself reflected in coverage, Googoo says, but most outlets don’t realize that. She was tired of reporting for non-Aboriginal editors and producers in her various positions (outside of APTN). Yes, there were other reporters, but she asks, “Where are the Aboriginal decision-makers?” Without them, stories about Indigenous people can be the first to be cut.

For Googoo, the solution was to tackle the problem head-on by creating her own website. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a conversation to be had: we should be talking about diversity in the newsroom and in journalism education. Coverage of Indigenous issues in mainstream outlets has been developing, she says, but there’s still room for improvement. More reporters are making an effort now to get things right about Indigenous culture. But sometimes, she says, it takes a crisis for journalists to turn their gaze to Aboriginal communities.

Let’s Stop Pretending

Vice reporter Manisha Krishnan says Canadian society needs to realize its flaws to do something about them

Frustrated by this, she focused her journalism on under-represented groups. The staff writer for Vice Canada has covered discrimination against LGBT groups, women and various cultures and races. She wants to shine a light on a different side of stories and often sees “systemic factors at play.” She picks them apart for her readers.

Krishnan is skeptical of the idea that Canada is a discrimination-free society and feels fortunate to be able to write stories that show this isn’t the case. Vice also gives her the freedom to insert her opinion into stories. In an article about how the Alberta government released recommendations for schools to make their transgender students feel comfortable—“a good thing,” she writes—Krishnan describes the “absolute shitstorm” that ensued among members of the population who were against progressive developments such as gender-neutral spaces in bathrooms. She writes that studies show one-third of Canadian trans youth have attempted suicide. She hopes showing the discrimination makes articles about systemic problems powerful.

Krishnan also received a lot of attention for “Let’s Stop Pretending the Guy Who Pepper Sprayed Syrian Refugees Doesn’t Reflect Canada.” In it, Krishnan asks how Canadians can possibly argue that xenophobia is not present here. She received many comments on the piece that started a serious conversation on the topic and, later, a few radio shows interviewed her about it.

Words Hurt

Buzzfeed Canada reporter Lauren Strapagiel says the trauma of sexual assault is amplified when reporting uses the wrong language

Femifesto, the Toronto-based feminist organization that published the document, told Strapagiel it was being revised and asked her to be part of the advisory committee. The new version was published in December 2015 and was called “Use the Right Words: Media Reporting on Sexual Violence in Canada.” It outlines how to interview survivors of assault and the correct language to use in such stories. It also educates on rape culture, discussing concepts like survivor blaming and the sexism ingrained in society—elements of women’s issues Strapagiel has often written about.

During the Ghomeshi trial, Strapagiel observed how many journalists picked up the narrative she saw presented by his lawyer Marie Henein—a narrative meant to discredit the witnesses and place blame on them. When Henein produced a letter to Ghomeshi from witness Lucy DeCoutere in court, she did so theatrically, carefully crafting the way it was received. “Media coverage used that same language, calling it a ‘handwritten love letter,’ and acting like it was this big moment,” Strapagiel says. “Which is exactly what the defence would want. And I feel like people played right into it.”

She says that unlike many newsrooms, BuzzFeed promotes diversity and inclusion, and she’s able to write about things she’s passionate about. “I’m actively encouraged to cover LGBT issues,” she says. “We set goals around it.” While there are different definitions of the word “diversity,” Strapagiel believes it means having a range of backgrounds, viewpoints and identities. “Newsrooms can show great diversity, but I think it’s important it translates to the actual work being put out.”

There’s a fine line between utilizing diversity and labelling someone based on an aspect of his or her life. “In any newsroom, when you are identified as ‘the gay reporter,’ or ‘the Black reporter,’ or ‘the diversity reporter’ or whatever—you want to cover these things because you understand the importance of them, but you don’t want to get pigeonholed,” Strapagiel says. “And that’s a struggle that I still haven’t figured out.”

Out of the Unordinary

Carol Sanders of the Winnipeg Free Press rejects the label “diversity reporter” in an era when all reporting should be diverse

It was a mark of trust for a reporter who worked for many years to build it since graduating from creative communications at Winnipeg’s Red River College in 1987. After working in radio in B.C. and then at the Thunder Bay Chronicle-Journal, Sanders became a copy editor for the Free Press in 1997 before returning to reporting in 2000. She’s still just a general assignment reporter, she insists, though she’s unofficially the paper’s diversity reporter. “Diversity is just a title that’s been slapped on,” she says. But it’s a term she dislikes—all reporters should be diversity reporters.

Until 20 years ago, Winnipeg’s lack of diversity was so severe that, according to Sanders, someone from Portugal or Italy was considered exotic. After 9/11, Manitoba witnessed a large influx of newcomers from around the world. But no one covered these new communities except when something bad happened, perpetuating negative stereotypes and distancing these groups from journalists. It was an Islamophobic time, and reporting involved a lot of rent-a-quote from people who were otherwise ignored by mainstream media or vilified. There was no bridge-building, she says, adding emotionally, “It made you want to cry.”

Sanders was covering a shooting fatality when a leader of the Punjabi community refused to talk to her. “He was the first person to say something,” she says. He didn’t trust her and he didn’t feel safe talking to her because he knew the report would just make his community look bad. “You need to build up some trust,” he said.

So Sanders formed connections among the various ethnic groups in Winnipeg. Trust gave her access to the Eritrean community, enabling her to report on how they were coerced to pay a diaspora tax to a regime they fled. In December 2011, about 100 Eritrean protesters demonstrated outside the Free Press, upset that Sanders’s stories portrayed them all as having terrorist links. Then-editor Margo Goodhand met with protesters, listened to their concerns and explained the newspaper’s side of the story.

Journalists should help readers get to know the people in their communities in order to make them less scary, according to Sanders. And that means doing more than just the big news stories. “Go and do the fluff,” she says, “because it’s not the fluff that’s the important thing, it’s the people—it’s the contacts, the connections you make.”